The Birdhouse Man, P2

Two Stories About Family and Reclaiming a Neighborhood, Told A Decade Apart

A decade ago, I wrote the essay that we published yesterday, Part 1. You can read that here: The Birdhouse Man, P1.

Today, a decade later, we continue that story in conjunction with Manchester Ink Link. This is a story I’ve been wanting to finish for, well, ten years, but never had the chance in part because I was afraid that it wouldn’t have a happy ending. Turns out, I didn’t have to worry.

Tell me what you think, and thank you for being part of this journey. Today, Part 2 of The Birdhouse Man.

THE BIRDHOUSE MAN, PART 2

Summer, 2024

I’m holding my breath.

After ten years, I’ve returned to my grandmother’s house, this time with my family in tow. I don’t know how this is going to go.

I have some trouble finding the house at first, trying to remember the street name, zig-zagging through a neighborhood that has fallen into disrepair and decay.

As a child I walked these streets with my cousins, with my mother – to a little market on the corner, to a playground down the block. The last time I was here was four months before my daughter was born. What is waiting for us – for her – now?

“This isn’t so bad,” my wife says. She’s heard my stories about the last time I was here, about my fear and sadness about the crumbing neighborhood. But then I realize we’re on the right street, and she’s right.

It’s better. This block is better. The homes are occupied. The grass is cut. There are flower beds and fresh paint.

And there is a home absolutely covered – covered like a blanket, from the street to the porch to the driveway – in birdhouses. Large and small, elaborate wooden castles, small dainty one-hole shoeboxes. We’ve found it. We’ve found my grandmother’s home again.

We’ve found the birdhouse man.

“Oh wow,” Little Bean says pressing her forehead against her window.

And once again, after ten years, I pull over in front of the house and am confronted by a young man, maybe early twenties who is just getting into his car.

“Can I help you,” he says.

It’s the Birdman’s son, again. That’s the same thing he asked me ten years ago when he was right there when I pulled up. He’s there today, ten years older.

“Hi,” I say, “you and I, we met ten years ago…” And I begin the story. He obviously doesn’t remember me, but he humors me. I mention that when I met his father ten years ago, he wanted to build a chicken coop.

The (still) young man smiles. “He did,” he says. “I have to go, but just go up the drive, through the gate. He’s in his workshop in the back yard. Tell him I told you to go.”

The three of us walk up the side drive, a drive that I walked up hundreds of times as a child, unlatch a gate and walk through a valley of huge birdhouses. And by huge, I mean some of them are taller than Little Bean.

“Hello,” I call out.

The garage in the back yard is new, as is the garden. To the left is a fenced in chicken coup, the same place my grandfather kept his chicken coop. John comes out of his workshop, older, heavier, but then again so am I.

“John?” He nods. I begin my story again, this time with my daughter and wife at my side. He still doesn’t know much English, but he knows enough. I doubt he remembers me from ten years ago.

“This is your daughter?” he says.

“Hi,” she says.

“Hang on, let me close shop, go back around to the front and I’ll meet you there.”

Little Bean runs ahead, back out through the gate and I hear someone say, “Who are you?”

It’s John’s wife and, I assume older daughter, who must have heard her and came out. So, I begin my story a third time. The young woman understands English perfectly and she translates to her mother.

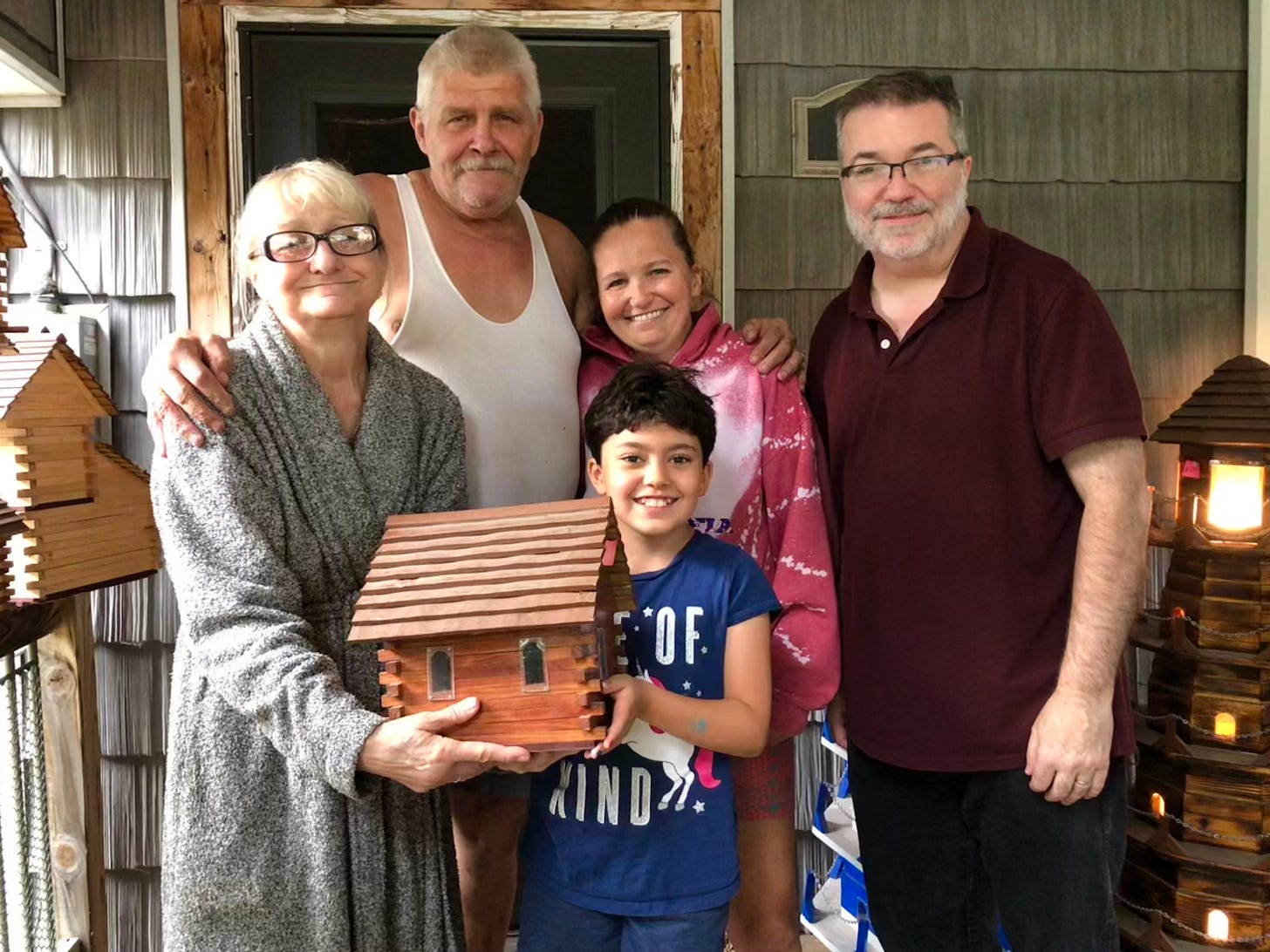

And right there on the porch of my grandmother’s old house, that perfect stranger grins and throws her arms around me. “Your grandmother!” she says.

She hugs Meena and Little Bean and then John joins us. Through our conversation, she keeps her hand on my elbow.

I talk about the corner store just up the street, the church around the corner where my parents were married. I tell them that my parents lived on the second floor after they got married; that my cousins would walk with me to the nearby railroad tracks where we’d collect rocks.

The younger woman translates.

They ask where we live now, what’s become of our family. They talk about how they are trying to bring back the neighborhood, how hard that’s been.

“It looks better,” I say, “so much better than when I was here ten years ago.”

John smiles. Like last time, he’s a man of few words and he seems done with the conversation. He turns to Little Bean and says, “Follow me.”

The two of them walk up onto the porch where there’s two dozen different birdhouses in different shapes and sizes. “Pick one,” he tells her.

She looks at me and I reach into my pocket for cash.

“No,” John says, “no no. Let her take one. From us.”

I can only nod, if I say something my voice will crack. I watch as she looks over the birdhouses, praying she won’t pick the one that’s the size of a washing machine. She lifts up a normal sized house, one room with a steeped roof. It’s lovely.

“It’s yours,” John says.

“We’ll put it in our own garden,” Meena tells him.

As the ladies pack the birdhouse into the car, I have a moment alone with John. “Are you sure,” I say. “I feel bad-”

He puts his hand on my shoulder and shakes his head. The matter is settled.

We all promise to stay in touch. John’s wife hugs us again. On the way out of the neighborhood, I point out some landmarks: my cousin’s old house, the deli where my uncle would take me for treats, the central post office and the huge Central Terminal Train Station, now abandoned but with plans on the table to bring that back as well.

And in the back seat next to Little Bean, a brown, wooden birdhouse built by the man who now is where I used to be, whose family is trying their best, like ours - the group of us brought together by common architecture and ancestry in a broken neighborhood with broken English.

Gossamer tendrils across time, running through neighborhoods like ghosts, echoes of where we were and where we’re going and all closer than you’d expect. A bird house, made by a Polish man, now hanging in our backyard, and every time I see it, every time Little Bean passes it by, we’re reminded of my grandmother.

That birdhouse makes the world a little smaller and a little more intimate. History doesn’t seem so far away, the path forward is now clearer. One simple, wooden birdhouse drawing a line between so much that’s come and so much that remains.

We are all, every one of us, connected.

Such a tender, love-filled story. And so beautifully written. It touched my heart.

What a beautiful story! I've been looking forward to seeing how this turned out.