Today, we celebrate the 90th anniversary of the biggest wind on the planet. Literally!

In the early morning of April 12, 1934, Mount Washington Observatory observer Wendell Stephenson pulled on his parka and storm pants and stepped outside into a maelstrom. About 4 a.m. that night, the observatory’s anemometer had iced up (or been knocked clean off the roof) and somebody had to go outside and see what was up.

The University of Chicago graduate who was enjoying his second year as an observer for the grand sum of $5 a week, fought his way up a ladder to the roof and knocked the ice off the precious device with a crowbar.

Once back inside, the anemometer started ticking again, one tick for every 5 mph of wind speed.

“It was ticking so much it sounded like a telegraph,” Stephenson would later recall.

160… 170… 176… By 7am that morning, the highest wind speed to that point had already been beaten, and the ticks kept coming. Wind pressure on the observatory increased. The building began to ice up. The men inside the observatory gathered around the instruments, both excited about the increasing wind and terrified that the building would blow away.

At 1:45pm on April 12, the anemometer peaked at 231 miles per hour, a record of the highest gust of wind measured by humans that stands today.

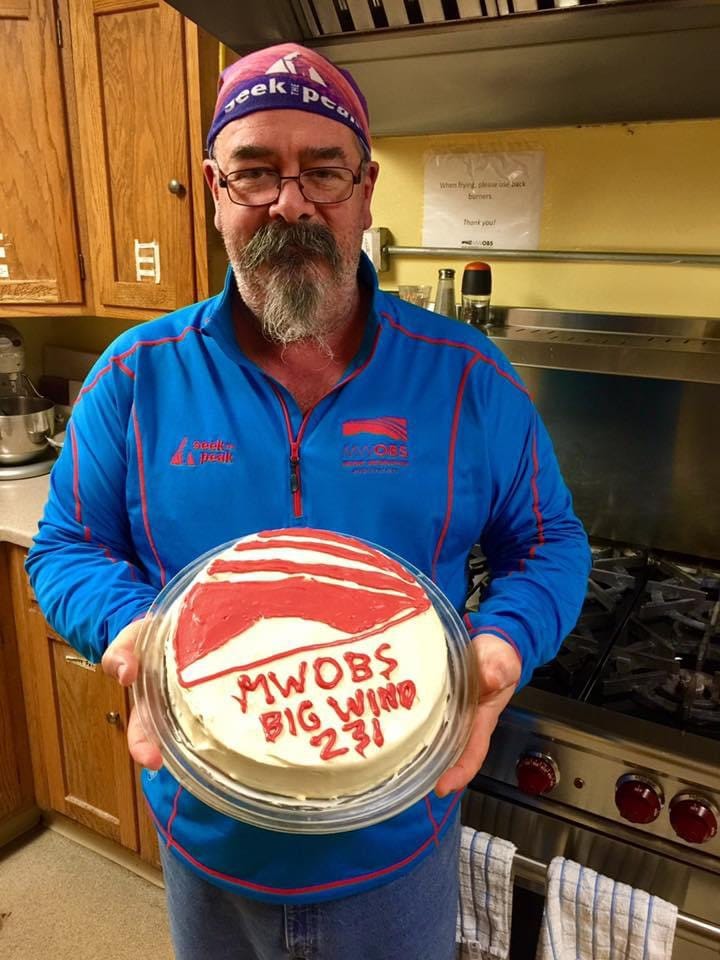

Each year, Mount Washington Observatory and lovers of that mountain mark the day with different sorts of celebrations. During my week long service at the summit, my volunteer-mate John Donovan baked a Big Wind cake that we all devoured!

Here’s what I wrote about my own wind experience atop the mountain in my book, The White Mountain:

Standing here in only eighty-five mile per hour winds, I can’t even begin to imagine how nearly three times this must feel. I’ve shuffled maybe ten feet out onto the deck, my head down, arms in front of me to keep them from flapping. This feeling is all about pressure. There’s pressure on my shoulders and head, as literal a feeling as if someone was standing in front of me pushing. I’m certain that if I just stood up and let go, I wouldn’t go tumbling, but I’d certainly be knocked down.

My goggles are beginning to frost up. For a split second, I think of taking a glove off to wipe them, then check myself. Don’t be an idiot, I think. My black parka is starting to coat with rime ice, long white streaks along the front of my parka chest and arms. There’s enough moisture in the air that I can stand here and watch the rime form on my body.

If I stood here long enough, I’d turn into one of those rime sculptures that forms on trail signs or on the weather equipment, long tendrils of snaking ice, delicate strands collecting on my fingertips and off the top of my head—an organic testament to living air.

And so, the observatory continues its work and the men and women continue in the footsteps of the founders, measuring, observing keeping the faith that at some point, some night their (now) digital equipment will start spinning and another record will be broken.

Until then we turn to Shakespeare for the last word on wind: “Blow, blow, thou winter wind / Thou art not so unkind / As man’s ingratitude / Thy tooth is not so keen / Because thou art not seen / Although thy breath be rude.”

Stay out of the wind my friends, but if you must be in it, then stay low and stand firm.

On my first Edu-Trip to the Summit we eagerly couldn't wait to go outside...wind was howling, broken clouds. Leader Bryan Yeaton advised us: "It's blowing 107, don't try to stand up, stay bent over, preferably butt first!!" After exiting the building we were all flattened to the ground...Bryan wasn't kidding. I cannot even imagine twice that!